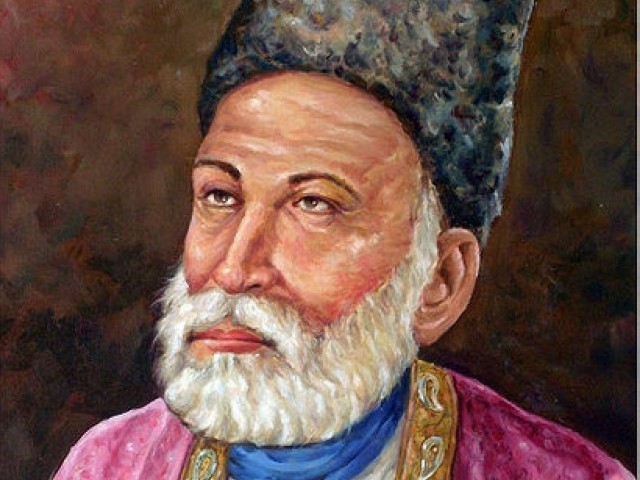

On Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib’s birth anniversary, I’m tempted to write about an unpublished ghazal that I came across very recently. When Ghalib compiled his Urdu deewan (collection of poetry), he was quite ruthless in selecting the verses that were deemed worthy of publishing. There are very many couplets and ghazals that he kept aside simply because they did not meet his own exacting standards. Just to give you an idea of the kind of ‘editing’ he did, only 234 Urdu ghazals made it to his deewan as opposed to 441 that are known to exist. Add to that the countless couplets from his published ghazals that did not make the cut. Many such unpublished verses later came to light through the efforts of people like Arshi, Gyan Chand Jain and Kalidas Gupta ‘Raza’.

I came across this ghazal when I bought a compilation of Ghalib ghazals sung by Pakistani artistes. I had never read this one before, so I quickly opened my copy of Deewan-e-Ghalib to read the complete ghazal. I searched, and I searched, but how could I find it there? It was an unpublished ghazal afterall (unpublished may not be the right word to use as Raza did publish many of these a few decades back).

Here is that ghazal. I have made a feeble attempt at interpreting the same, but I cannot say for sure if I have been able to get them totally. Ghalib’s poetry has so many layers that it is impossible for me to get all of them in a few readings.

ख़बर निगह को निगह चश्म को 'उदू जाने

वो जलवह कर कि न मैं जानूँ और न तू जाने

(ख़बर = awareness; निगह = sight; चश्म = eye; 'उदू = enemy)

This couplet is seemingly based on the premise that for any event to register in the mind it has to traverse the path from the eye to the sense of sight, and finally to the mind as awareness. What if the sense of 'awareness' is an enemy of ‘sight’, which in turn is an enemy to the ‘eye’? Will the 'eye' share an occurrence with its enemy i.e 'sight'? And even if that happens, will the ‘sight’ let the mind be 'aware' of it? Isn’t this a very complicated way of expressing a simple thought that the lover does not want the beloved to make a spectacle of her beauty. If at all, it should be done in such secrecy that even the lover does not get to know of it. I’m sure there is more to it, but I haven’t got it yet. Or maybe there isn’t and hence Ghalib discarded it.

नफ़स ब नालह रक़ीब ओ निगह ब अश्क 'उदू

ज़ियादह इस से गिरफ्तार हूँ कि तू जाने

(नफ़स = breath; ब = for; नालह = lamentation; रक़ीब = enemy; अश्क = tears; 'उदू = enemy)

Here Ghalib carries forward the same metaphor of two enemies. The lover is possibly telling the beloved (or could even be any third person), “You can never sense how badly troubled I am. You can at best hear my laments or see my tears, but can you sense how they affect me? My tears cannot coexist with my sight, and my breath cannot share the same space as my lamentations, just like when two enemies come face to face, one must perish. The extent of my troubled existence is such that my I cannot see (things that I hold dear) or can even breathe (the basis of my existence). In other words, it’s not merely my tears and laments that you see, what you see is a lifeless me.”

Now, the cause for the troubled existence is left to one’s imagination. Is it because of lack of reciprocity in love, or the beloved who is feigning ignorance to test the intensity of the lover’s feelings, or some impediment in the path of love, or something totally different? Figure it out yourself.

ब किसवत-ए-अरक़-ए-शर्म क़तरहज़न है ख़याल

मुबाद हौसलह म'अज़ूर-ए-जुस्तजू जाने

(किसवत = garb; अरक़ = perspiration, sweat; क़तरहज़न = running quickly; मुबाद = God forbid, lest, by no means; हौसलह = courage; म'अज़ूर = excused from, helpless; जुस्तजू = search)

This one has me foxed. It is one of those verses that slips out of your grip as soon as you think you have got it. The first line, as I see it, is another way of expressing the idiom शर्म से पानी-पानी होना. What makes this one a little difficult to understand is the question as to what is it that is making the poet so ashamed. And then the second line totally throws one off-guard. Could it be that the poet has given up the courage to search for something and is so ashamed of this fact that he is perspiring, but hopes that the others believe that the perspiration is due to the hard work he has been doing in that search? Or in other words, hoping that his failure is mistaken for genuine effort? Or maybe there is in fact a genuine effort, but the results are not forthcoming, hence the shame? These lines are still ambiguous in my mind. Maybe someone can help me get a better handle on this.

What I find interesting is the use of the word क़तरहज़न for ‘running quickly’, which works beautifully against the imagery of drops (क़तरह) of sweat (अरक़)

ज़बाँ से 'अर्ज़-ए-तमन्ना-ए-ख़ामुशी म'अलूम

मगर वो ख़ानह-बर-अंदाज़ गुफ़तगू जाने

('अर्ज़-ए-तमन्ना-ए-ख़ामुशी = expression of the desire to be silent; म'अलूम = Known, evident; ख़ानह-बर-अंदाज़ = a metaphor for the beloved; गुफ़तगू = conversation)

At first, this verse appeared very straightforward to me. But on careful reading, multiple meanings emerged depending on how one looks at ख़ानह-बर-अंदाज़ and whose silence or conversation is being talked about. The first two meanings assume the metaphorical meaning of ख़ानह-बर-अंदाज़ i.e the beloved. There could be multiple interpretations depending on who that subject is and whose silence is being talked about.

- Let's first look at it this way. The lover wants some alone time and can express his desire to be silent in words, but the beloved cannot understand that. The very fact that the lover has opened his mouth to say something, even if it is the desire to remain silent, the beloved would assume it to be the start of a conversation and the lover's desire for some solitude will not be fulfilled.

- Alternatively, one could look at the request for silence as being directed at the beloved. Can the beloved who is interested in a conversation pay heed to the lover's request for silence?

- A completely different meaning emerges if one considers the literal meaning of ख़ानह-बर-अंदाज़ as someone who destroys a home through his spendthrift nature, a sort of a curse. In other words, one knows how to request the tongue to keep quiet, but the cursed tongue only knows how to talk and squander away the 'wealth' of thought. The request for silence could be with the intent of keeping a secret / hiding the truth, which the tongue blurts out. Or, the intent could be for some peace and quiet to reflect over things, which is difficult to achieve if one is by nature drawn to a conversation.

गुदाज़-ए-हौसलह को पास-ए-आबरू जाने

(जुनूँ = passion; फ़सुर्दह = frozen, cold; तमकीं = power; 'अहद-ए-वफ़ा = promise of allegiance; गुदाज़ = melted, not firm; हौसलह = courage; पास = regard; आबरू = dignity)

Two meanings emerge from this. The difference is subtle. One, the lover’s passion has grown cold and has lost its power, but the lover does not want to call it quits yet and hopes that the beloved (personifying the promise of allegiance) mistakes the lover’s dithering courage to express his passion for his regard for maintaining dignity. Here, the relationship has probably started going on a downward spiral, but the lover does not want to quit yet and hopes the beloved lives under a false impression till the situation is resolved. The other way of looking at this could be that the lover says that the apparent dying of passion is not real and is just a manifestation of his regard for maintaining dignity, and hopes that the beloved understands that and doesn’t suspect his allegiance.

What I find interesting in this couplet is the use of the words फ़सुर्दह and गुदाज़, which at one level are opposites ( frozen vs. melted), but signify the same thing.

न होवे क्यूँकर उसे फ़र्ज़ क़त्ल-ए-अहल-ए-वफ़ा

लहू में हाथ के भरने को जो वुज़ू जाने

(फ़र्ज़ = duty; अहल-ए-वफ़ा = lovers; वुज़ू = ablution (a religious ritual))

For someone who considers washing his hands in blood to be as pure as ablution, killing of lovers is but a ‘duty’ for him. What exactly is going on here? This one seems too trite to me. Am I missing the underlying implications?

मसीह-ए-कुश्तह-ए-उलफ़त बबर 'अली खाँ हैं

कि जो असद तपिश-ए-नब्ज़-ए-आरज़ू जाने

(मसीह = a person who can sure illness; कुश्तह = slain, a form of herbo-mineral preparation used mostly as an aphrodisiac in the Unani system of medicine; तपिश = fever, agitation; नब्ज़ = pulse; आरज़ू = desire)

I found this a very odd couplet as I had no clue who Babar Ali Khan was? After some search I came across two references to Babar Ali Khan. First one was in one of Ghalib’s letters to the Nawab of Rampur in the summer of 1865. On hearing about the Nawab’s ill-health, Ghalib writes a detailed letter to him telling him about some cures and a fairly elaborate diet plan. There he mentions the recipe of an old hakeem by the name of Babar Ali Khan. The other reference I got was in the history of Murshidabad, where Babar Ali Diler Jang is mentioned as the Nawab of Murshidabad from 1796-1810. I would have dismissed this as just a case of two men with similar names, till I read this line about the Nawab,

“He was very fond of tonics, in the shape of kushtas. He always searched for and inquired after Jogis and others who were experts in the making of kushtas”

Now it gets interesting… Although the place where I read about the Nawab of Murshidabad doesn’t refer to him as a hakeem, it is possible that Ghalib is referring to the same person. Even if that is not the case, the search for the Nawab took me to the other meaning of kushta, which makes this seemingly simple verse resonate with a Ghalibian touch - a wordplay between the two meanings of kushta - slain (i.e.a lover) and a recipe for an aphrodisiac.

Now let’s look at the verse. It simply says that Babar Ali Khan has a remedy for lovers (those ‘slain’ in love) because he knows what can make the pulse of passion run fast - kushta - an aphrodisiac. This is a smart verse in that it makes use of both the meanings of kushta and also of tapish, which can imply both a fever/ illness (negative implication) and agitation/ excitement (positive implication in the context of love). But apart from that, there doesn’t seem to be much depth to it. Also, it is not clear why Babar Ali Khan is referred to in this verse. Was he that famous a man during Ghalib’s time? Even if he was, since the name is long forgotten now, the verse too cannot stand the test of time.

Here are four verses of this ghazal in the voice of Samina Zaidi

Another recurring character that has been a favorite of poets from time immemorial, and which found its way into Pt. Indra’s work as well, is the moon. I must add that he mostly stuck to the conventional roles of the moon, and I don’t find any innovative invocation of the moon in his work. His moon is fairly comfortable wearing the conventional garb. It becomes a messenger in ‘chanda desh piya ke ja’ (Bharthari 1944) or ‘sheetal chandni khili khili’ (Draupadi 1944), transforms into a close confidante in ‘o sharad poonam ki chandni’ (Gunsundari 1948), is advised not to cast an evil eye in ‘ae chand nazar na lagana’ (Moorti 1945), becomes a playful mate in ‘chanda khele aankh michauli’ (Jogan 1950), is equated to the beloved in ‘chanda chamke neel gagan mein’ (Bahut Din Hue 1954), is used a metaphor for beauty as well as accused of being a thief in ‘chandavadani sundar sajni’ (Man Ka Meet 1950), or simply transforms into an object decorating the mise-en-scene in a romantic song like ‘chanda chamkti raat’ (Do Dulhe 1955). And of course, a mother equating her child to the moon as she sings a lori cannot be far behind, as in ‘pyare more chanda ae mere ladle’ (Mangala 1950).

Another recurring character that has been a favorite of poets from time immemorial, and which found its way into Pt. Indra’s work as well, is the moon. I must add that he mostly stuck to the conventional roles of the moon, and I don’t find any innovative invocation of the moon in his work. His moon is fairly comfortable wearing the conventional garb. It becomes a messenger in ‘chanda desh piya ke ja’ (Bharthari 1944) or ‘sheetal chandni khili khili’ (Draupadi 1944), transforms into a close confidante in ‘o sharad poonam ki chandni’ (Gunsundari 1948), is advised not to cast an evil eye in ‘ae chand nazar na lagana’ (Moorti 1945), becomes a playful mate in ‘chanda khele aankh michauli’ (Jogan 1950), is equated to the beloved in ‘chanda chamke neel gagan mein’ (Bahut Din Hue 1954), is used a metaphor for beauty as well as accused of being a thief in ‘chandavadani sundar sajni’ (Man Ka Meet 1950), or simply transforms into an object decorating the mise-en-scene in a romantic song like ‘chanda chamkti raat’ (Do Dulhe 1955). And of course, a mother equating her child to the moon as she sings a lori cannot be far behind, as in ‘pyare more chanda ae mere ladle’ (Mangala 1950).