This piece is written by Archana Gupta. It first appeared as part of the Guzra Hua Zamana series on Sangeet Ke Sitare, a music group on Facebook.

दो निगाहों का अचानक वो तसादुम तौबा

ठेस लगते ही उड़ा ‘इश्क़ शरारा बन कर

...

अब शरारा यही उसके दिल-ए-बेदार में है

और 'कैफ़ी' मेरे तपते हुए अश'आर में हैAh! that sudden collision of two glances

Impact that sent a spark of romance soaring

…

Now that spark lives in her restless heart

And exhilaration in my scorching verses

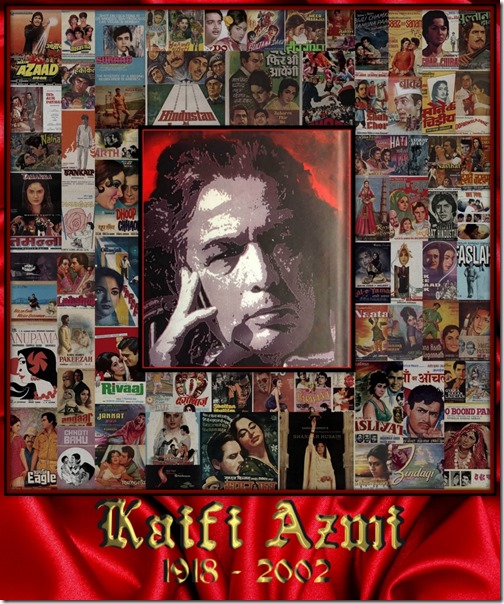

Kaifi, The Child – The Beginning

A child is born as a seventh child to a well to do, educated, and progressive thinking landowner and his wife. The father is way ahead of his time and has sent each of his older three boys to English schools to get a modern education and has himself decided to seek employment in the city of Lucknow, leaving his family occupation to his brother. A few years down the road, four beloved daughters of the family, sisters of this child succumb to tuberculosis, one after another. That convinces the parents that the calamities are a result of providing an English education to the older boys and they must get this child religious education so that he becomes a “Maulavi”. The child is confined to a life in the small village he was born in, kept away from a modern education and never learns any English. He is sent to a traditional Madrasa eventually but destiny has something completely different in store for him. What you ask? Well, I tell you that this child was Syed Athar Husain Rizvi, better known as Kaifi Azmi!

By most accounts, Kaifi Azmi was born on January 14th, 1918 in a very small village called Mijwan in Azamgarh district of Eastern Uttar Pradesh. However, he himself begins an autobiographical article stating that all he can say with surety is that he was born in pre-independent India, has grown old in independent India and will die in Socialist India! His early childhood was spent accompanying his mother who was busy running from pillar to post trying in vain to save the lives of her daughters. After the death of his sisters, he was assigned to helping his paternal uncle in the fields at a fairly tender age instead of being sent to school, while he was actually most interested in studying and would create a ruckus every time his brothers were to leave for school at the end of a break.

While the parents wanted Kaifi to get a religious education so that at least one of their children will be able to perform “Faatihah” – prayers for blessings on the dead, his paternal uncle wanted him to get no education at all! To Kaifi’s utter dismay, he convinced Kaifi’s father, Syed Fatah Husain Rizvi, to let the child help out in the fields. One fine day, their largest field was to be cut and uncle had to go out. Kaifi was left in charge with strict instructions to not allow any worker to cheat when keeping their own share aside. He got extremely distracted by a beautiful young lady worker and allowed her far more than her share of the grains. When the uncle returned, another old lady complained against Kaifi and the uncle was extremely upset. He told the parents that their son was unfit to take care of the family business/zamindari! It was as if fate intervened to fulfill Kaifi’s desire for an education as his parents packed him off to Lucknow for religious education at Sultanul Madaris, the largest Shia religious school in the city!

Kaifi, the Youth – Budding Poet & Comrade

Kaifi started his education at Sultanul Madaris as a boarding school inmate. Now he would go home only during holidays. Other than the fact that he was finally getting a formal education, this phase of his life was very notable on two counts. One, it was during these years that he started his own poetic journey and he was first introduced to progressive literature. Secondly, it was here that the seeds of Socialism and Communism were sown in young Kaifi’s mind and ideas like protesting against establishment/ unfair practices, etc. took root and even got put into practice. So, this was also the beginning of Comrade Kaifi’s journey. These two aspects – poetry and communist/socialist beliefs define the core of Kaifi Azmi’s personality and greatly influenced every other aspect of his existence.

While he had started his formal education rather late, Urdu poetry came naturally to him via the exposure through his own family. His father was not formally a poet himself but was very fond of poetry and the house was full of Urdu and Persian Diwans of several poets. All three of his brothers were proper “shu’ara” (poets) who sported a “takhallus” (pen-name) and maintained a “bayaaz”(notebook to jot down poetry). Whenever they came home for a break, poetry gatherings or she’ri mehfils /mushaa’iras would be arranged where several shu’ara from the whole district would participate. Little Kaifi would try and find excuses to hang around but was generally shunned and considered too young and too lacking in any knowledge to be allowed to even listen in. He was secretly very envious of the praise that his brothers’ poetry received from their father and yearned for some of it for himself. But his urge to participate in such activities was often stifled and he was asked to run lowly errands like serving paan, etc. Little did anyone know then that one day this child’s poetry would be recognized the world over, or that he will be counted amongst the most brilliant Urdu poets of the century and most talented lyricists in Hindi Film World.

He himself recounted an interesting and almost heartbreaking tale in the foreword of one of his poetry compilations. When he was about eleven years old, one such mushaa’ira was organized in Bahraich where his father was employed at an estate as tahsildar. It was a “Tarahi” mushaa’ira with “Meharbaan Hota” as the “Tarah”. This was the first mushaa’ira where he was allowed to recite and he recited a ghazal containing this she’r

वो सब की सुन रहे हैं सबको दाद-ए-शौक़ देते हैं

कहीं ऐसे में मेरा क़िस्स:-ए-ग़म भी बयाँ होता

Vo sab kii sun rahe hain sabko daad-e-shauq dete hain

Kahin aise mein mera qissa-e-gham bhi bayaan hotaa

The mushaa’ira was being presided upon by a well-known poet Syed Mani Jayasi and he really liked this she’r and asked for it to be repeated multiple times. Kaifi sahib recalls that while a lot of people said appreciative words to him, they all assumed and made it sound like the kalaam presented was written by one of his older brothers and handed to him to present as his own and comments ranged from “You have a sharp memory” to “You have recited very reliably and with confidence”. While these comments hurt Kaifi sahib, he was most bothered by the fact that his own father thought the same! When his brothers denied any involvement, it was decided he should be “tested” to see if the ghazal was his own creation or not! His father’s munshi, Hazrat Shauq Bahraichi was a satirist and provided the tarahi line on which Kafi was asked to write a ghazal. The misra was

“इतना हँसे के आँख से आँसू निकल पड़े”

“Itna hanse ke aankh se aansoo nikal pade”

The ghazal that Kaifi wrote in a very short while went

इतना तो ज़िंदगी में किसी की ख़लल पड़े

हँसने से हो सुकून न रोने से कल पड़े

जिस तरह हँस रहा हूँ मैं पी पी के गर्म अश्क

यूँ दूसरा हँसे तो कलेजा निकल पड़े

इक तुम कि तुम को फ़िक्र-ए-नशेब-ओ-फ़राज़ है

इक हम कि चल पड़े तो बहरहाल चल पड़े

साक़ी सभी को है ग़म-ए-तिश्नः-लबी मगर

मय है उसी की नाम पे जिस के उबल पड़े

मुद्दत के बाद उसने जो की लुत्फ़ की निगाह

जी ख़ुश तो हो गया मगर आँसू निकल पड़े

Now this ghazal may not be amongst the most stellar of his creations (and he certainly did not consider it so), considering that it came from an eleven year old’s pen, it is absolutely brilliant! And knowing this tale, one can well imagine that a few of these ash’aar (check the second one and the last one) probably describe his own mental state at the time of writing it. In any case, it convinced everyone that he had not cheated and had read his own ghazal. Now most references, even one of Kaifi sahib’s own interview claims this to be the first ghazal he penned but it seems quite obvious that this could only have been his second! In any case, while most of his early kalaam is no longer available, this ghazal survived and is well known also (as his first ghazal) as it was later immortalized by the incomparable Begum Akhtar!

After the break, when he returned to Lucknow, everyone around convinced him that to be a serious Shayar, he must have an Ustaad. He secured an audience with Maulana Safi and recited this same ghazal for him in the hope of receiving an islaah (correction or improvement). The master probably recognized the potential in the young lad’s pen and advised him to continue to read & write independently without getting swayed by the true or false praise that he may be deluged with. He simply considered himself too old and too staid to adequately provide islaah to such a young, intense and impassioned pen. Master’s words were “Agar tumhare kalaam mein zabaan ki kami hai to main use zaroor theek kar sakta hoon, lekin aisa karne se tumhare fikr kii garmii chali jaayegi… Meri ray ye hai ki agar waah waah se gumraah na ho to likhte raho. She’r kii kamiyaan sookhe patton kii tarah girtii chalii jaayengi aur khoobiyaan naii konplon ki tarah phootatii rahengi.” Kaifi sahib took the advice and did exactly that. Rest, as they say, is history!

As stated before, Kaifi Sahib was sent to Sultanul Madaris to get a religious education and become a Maulavi but it had quite the opposite impact on his young mind. He has stated in an autobiographical article of sorts that it was here he first understood the meaning of this Farsi couplet

मुफ़्तियान् क्-ईन जल्वः बर मिह्राब ओ मिन्बर मी-कुनन्द

चून् बि-ख़ल्वत मी-रवन्द, आन् कार-ए-दीगर मी-कुनन्द

Which roughly translates to

मुफ़्ती लोग *ये* जल्वा मस्जिद और मीनार के बीच दिखलाते है

(और/लेकिन) जूँ ही ख़लवत में जाते हैं "उस दूसरे काम" में लग जाते हैं

And clearly even when interpreted most innocuously, it is a comment on the fact that religious leaders rarely ever walk the talk, that they preach one thing and practice another. Kaifi Sahib’s comment indicates a strong disillusionment with the religious leadership and indeed, he was disillusioned with the school’s policies also, so much so that he incited and led a strike amongst the students that ultimately resulted in him being expelled from Sultanul Madaris. As Ayesha Siddiqi put it, “Kaifi Sahib ko unke buzurgon ne Sultanul Madaris isliye bheja tha ke wo Faatiha padhnaa seekh jaayenge. Kaifi Sahib wahaan mazhab par Faatiha padh kar nikal aaye!

During this strike, he started writing revolutionary poetry to instigate his fellow students and would write almost at the rate of one nazm a day! It was during this time that he was noticed by Ali Abbas Hussaini, a noted Urdu writer, who introduced him to Azam Hussain, then editor of a daily “Sarfaraz” who not only published one of his nazms in the paper but also wrote an editorial in support of the Students’ strike. He was also introduced to Ali Sardar Jafri, who was a key student leader and a position holder in Students Federation, and this was the beginning of a lifelong association. This external support gave a new impetus to Sultanul Madaris agitation. Eventually, the strike was called off after roughly 18 months once students’ demands were accepted.

However, in the process, several student leaders, including Kaifi Sahib, were thrown out of the school. Kaifi sahib had anyway, by this time, given up the idea of becoming a Maulavi, although he continued his education privately and appeared for several private examinations collecting various Urdu, Arabic & Persian language degrees from Lucknow & Allahabad Universities. Though he had initially intended to do F.A also and get an “English” education, by this point he was so involved in his poetry and politics that he gave up that idea.

During his years in Sultanul Madaris and subsequent time in Allahabad, he was greatly influenced by the Swaraj Andolan that was on in full force in Allahabad and participated in several related agitations. In 1935, First Conference of Progressive Writers Association was held in Lucknow and was presided over by Munshi Premchand. Kaifi sahib also participated in it and from then on was associated with the movement and remained an active member right till the end. Eventually, he landed in Kanpur and got connected to Communist Party, an association that lasted a lifetime and shaped a good part of the man, his mind and the rest of his life.

From Comrade Kaifi to Lyricist Kaifi – Life in Bombay

In 1942, he joined Mill Workers Struggle in Kanpur and this lead to some fiery, scorching verses like “Aakhiri Imtihaan”. He sent one of his nazms for publication to a Bombay based publication “Qaumi Jang”, an Urdu newspaper published by the Communist party. The editor, Comrade Sajjad Zaheer really liked it a lot and tracked him down to invite him to move to Bombay and work with him. Kaifi moved to Bombay and started work at the paper in 1943 for a monthly salary of R. 45/-. He was sure an official card bearing Communist Party member now. It was around this time that he got involved with Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) and Indian Peoples Theatre Association (IPTA) as well. At this point he was also an active participant in mushaa’iras and would travel far and wide for those or for other Party business.

In 1947, he visited Hyderabad for one such Mushaa’ira. Here, he was noticed by Ms. Shaukat who was visiting her sister and brother-in-law with whom Kaifi Sahib was staying along with a few other luminaries like Sardar Ali Jafri and Majrooh Sultanpuri. While she was generally impressed with his exceptionally good looks, deep and resonant voice and visually articulate gestures, she was particularly impressed with the boldness of the sentiments expressed in the Nazms he had chosen that day! First one was a Nazm against Taj Mahal and the other was a nazm that has now become synonymous with Kaifi Azmi and frankly, would be enough on its own to immortalize him even if it was the only piece of poetry he ever wrote – “Aurat”. The sentiments and the male view of the female expressed in Aurat is enough to blow a woman off her feet even in today’s world, let alone 70 years ago. The kind of encouragement and partnership it offers to the beloved is simply unparalleled. Kaifi sahib has gone on record saying that it is truly a representative of his personal views with respect to a woman’s role in life both in times of war and in times of peace. The Nazm simply encourages a woman to find and express herself freely, be a man’s equal, chalk her own path and traverse it shoulder to shoulder with her man or without him and not tie herself down or hold herself back in the name of customs, society, family or even love. Shaukat Sahiba has gone on record saying while every word was impressive, she was particularly moved by the following lines and remembers them to date!

ज़िंदगी जेहद में है सब्र के क़ाबू में नहीं

नब्ज़-ए-हस्ती का लहू काँपते आँसू में नहीं

उड़ने खुलने में है निकहत ख़म-ए-गेसू में नहीं

जन्नत इक और है जो मर्द के पहलू में नहीं

उसकी आज़ाद रविश पर भी मचलना है तुझे

उठ मेरी जान मेरे साथ ही चलना है तुझे

She asked for his autograph after the mushaa’ira and that was when he first noticed her. Gradually, their attraction grew and they started writing to each other (she was in Hyderabad and he in Bombay). One sees strong shades of the romantic side of Kaifi the poet in his real life romance too. A good example is found in an utterly filmy incident – Apparently, once Shaukat Sahiba got upset at Kaifi Sahib and they had a lovers’ spat. In response, he wrote a beautiful love-letter to her with a pen soaked in his blood in an effort to convince her of his sincerity! It certainly shook her up and though her father tried to calm her down by telling her it must be the goat’s blood that Kaifi used, the lady was more than won! Who could resist a man who signed pledges of never-ending devotion in blood and promised equality and partnership hitherto unheard of in fantastic verses! One wonders could a romance have been better executed even in a planned Bollywood film! It should then be no surprise to anyone that this whirlwind courtship had a predictable, fairytale ending – despite the social and ideological differences between her family and Kaifi Sahib and despite the fact that she was engaged to another, Shaukat Sahiba married Kaifi Sahib the same year and moved to Bombay.

Almost no sooner was the knot tied than its strength was put to test by the reality of life as Communist party members. Kaifi Sahib lead a life of austerity that only allowed for basic subsistence –he made Rs 45/- and paid Rs. 30/- for the one room quarter and a bathroom shared amongst 10 families, and his food from the commune kitchen. There was not even enough to pay for Shaukat Sahiba’s food. So he started writing nazms on demand at the rate of Rs. 5 per nazm and wrote one per day, all of which are no longer traceable or available!! This brought him enough money to pay for her food and have some to spare, but still there was never enough. Meanwhile, a baby boy was born to the young couple who lived only for a few months before succumbing to then prevalent illnesses like typhoid and pneumonia. This loss impacted Shaukat sahiba a lot and likely left a mark on Kaifi sahib as well.

A few months later, when Shaukat sahiba got pregnant with Shabana, Kaifi sahib woke up to the realization that children and extension in family implies additional expenses. On his friends’ advice, he took up Shahid Latif’s offer to write songs for his film and wrote two and a half songs for Shahid Latif’s 1951 film Buzdil. For this, he was paid a princely sum of Rs. 1000/- This marked the start of next major phase in his life and career!

Kaifi, the Artiste Extraordinaire

After Buzdil, Kaifi penned most of the songs of Bahu-Beti in 1952. This was primary a Geeta Dutt soundtrack with music by S. D. Batish. While it was easy to imagine a bonafide Urdu poet penning songs of Buzdil, several of the Bahu-Beti songs are very folkish in lyrics, be it the preening “Chhumak Chhumak Mora Baaje Ghungharva”, humorously teasing “Gori Dulhaniya” or the decidedly naughty “Mose Chanchal Jawaani Sambhali Nahin Jaaye”. These songs provided an early window into the versatility of Kaifi Sahib’s pen! In the following years he penned a one or two songs of several films like Gulbahar (1954), Hatimtai Ki Beti, Naata, Sakhi Hatim, and Shahi Chor (all 1955), Laal-e-Yaman, Sultana Daku, Yahudi Ki Beti, and Zindagi (all 1956), Jannat (1957), Chandu (1958), etc. but all of these films tanked big time at the box office and took the songs also down the drain along with them. Despite some being excellent songs, very few are remembered by even the old Hindi film music enthusiasts today.

Despite writing good songs, Kaifi Sahib’s films saw little commercial success and Kaifi Sahib came to be known as “unlucky”, a belief that seemed to get further validation by dismal performance of next several releases like 40 Days (“Baithe Hain Rahguzar Pe”, “Naseeb Hoga Mera Meharbaan”), Apna Haath Jagannath (“Chhayii Ghata Bijli Kadki”), Ek Ke Baad Ek, Razia Sultana, Bijli Chamke Jamuna Paar, Gyarah Hazaar Ladakiyan, Naqli Nawab, etc. Two 1961 releases fared much better musically – Shama composed by Ghulam Mohammad (“Dhadakte Dil Ki Tamanna”, “Aapse Pyar Hua Jata Hai”, “Ek Jurm Karke”, “Insaaf Tera Dekha”, and “Mast Ankhon Mein Shararat”, etc.) and Shola Aur Shabnam composed by Khaiyyam (“Jeet Hi Lenge Baazi”, “Jane Kya Dhoondti Rahti Hain”). These songs proved to have an everlasting appeal and are popular to date but this did little to counter the label of “Unlucky” and work became a bit sparse.

The turning point in Kaifi Sahijb’s career came when Chetan Anand approached him to write the songs for his multi-starrer “Haqeeqat”. People warned Chetan Anand to not sign Kaifi but he quipped that he himself is considered unlucky so may be two negatives will make a positive together! And what a prophetic comment that turned out to be! Haqeeqat turned out to be a super hit, the music gained immense popularity, establishing Kaifi-Madan Mohan-Chetan Anand as a team that produced films with great music together - thrice again though with varying degrees of box-office success – Heer Ranjha in 1970, Hindustan Ki Kasam and Hanste Zakhm in 1973. The songs of these films are guaranteed to be instantaneously recalled by almost any old HFM enthusiast as soon as one mentions Kaifi sahib. After all who can forget the eternally inspiring “Kar Chale Ham Fida Jaan-o-Tan Saathiyo”, the desolate “Main Ye Sochkar Uske Dar Se Utha Tha”, the self-comforting “Hoke Majboor Mujhe Usne Bhulaaya Hoga”, utterly delightful “Zara Si Aahat Hoti Hai” or the patriotic “Hindustan Ki Kasam”, the very romantic “Har Taraf Ab Yahi Afsane Hain “, the ultimate declaration of devotion ” Hai Tere Saath Meri Wafa” or the softly sentimental “Tum Kya Jaano Tum Kya Ho”, naughtily teasing qawwali “Ye Maana Meri Jaan Muhabbat Sazaa Hai”, the very eagerly anticipatory “Betaab Dil Ki Tamanna” or the unimaginably poignant “Aaj Socha To Aansoo Bhar Aaye”. This last one is a beautiful ghazal that portrays extreme pain of the character with words like

रह गयी ज़िंदगी दर्द बन के

दर्द दिल में छुपाए छुपाए

and

दिल की नाज़ुक रगें टूटती हैं

याद इतना भी कोई न आए

Certainly words that bring the pain alive for the listeners. Using such a short meter so effectively is a sure sign of a master poet in action!

Heer Ranjha, incidentally, also marks an exclusive feat in Kaifi Sahib’s film repertoire, or even in Hindi Cinema, a feat that goes much beyond song-writing or script/dialog writing, both of which Kaifi Sahib had done before. Heer Ranjha was a unique concept in Chetan Anand’s head that he had tried executing before with different lyricists but failed - he wanted all the dialogs for the film to be in verse form but had not found a poet/lyricist who could deliver what he wanted to his satisfaction and the project was lying abandoned. After the success of Haqeeqat and its music, his hopes of bringing this idea to fruition resurfaced and he asked Kaifi Sahib to work on this project. Kaifi sahib delivered absolutely on expectation and the film was made. Unfortunately it did not jive as much with the audience and Kaifi sahib never got as much credit or recognition for this unique feat. The songs of the film, on the other hand, were much liked, be it the feathery soft touch of “Meri Duniya Mein Tum Aayiin” or the loud wail of “Ye Duniya Ye Mehfil” or the energetic, unabashed claim of “Milo Na Tum To Hum Ghabraayein” or the poignant heartbreak of “Do Dil Toote, Do Dil Haare”.

Haqeeqat heralded an extremely successful phase in Kaifi Sahib’s career as a lyricist that was marked by films with some evergreen songs and collaborations with the popular and not so popular Music Directors of the time, like Kohra, Faraar and Anupama with Hemant Kumar, Aakhiri Khat and Sankalp with Khaiyyam, Satyakaam with Laxmikant Pyarelal, Uski Kahani with Kanu Roy, Do Boond Paani with Jaidev, Pakeezah (“Chalte Chalte” only) with Ghulam Mohammad and Naina with Shankar-Jaikishan, etc. He won the National Film Award for Best Lyrics for the song “Aandhi Aaye Ke Toofan” of Saat Hindustani in 1969

In February 1973, he suffered from a paralytic attack and it appeared that that may just be the end of Kaifi Sahib’s active career. But that did not turn out to be the case at all. His will power and internal strength was far more than the potency of his disease. Just five days after the attack, when he regained some of his faculties, he dictated a nazm called “Dhamaka” to Shama Zaidi capturing the explosion he had felt in his head. In the same month, even before he was released from the Hospital, he wrote a nazm called “Zindagi” that is counted amongst his choicest nazms – sign of a very positive personality and a bonafide artist.

His non-Hindi Film ventures include Bhojpuri songs of Balma Bada Nadan, a Bhojpuri film in 1964 and a couple of songs for a Bengali film Aalor Pipasha (songs were in Hindi/Urdu) in 1965. Both these films featured Hemant Kumar as the music director.

In terms of style and versatility, Kaifi sahib’s oeuvre could compete with the best in HFM world. Besides language spectrum that was already pointed out, the genre range is fairly wide too. He has ghazal as a basic tool that he has used effectively as romantic songs like “Dhadakte Dil Ki Tamanna Ho Mera Pyar Ho Tum” and “Bahaaro Mera Jeevan Bhi Sanwaaro” at one end and heartbreakingly sad songs like “Aaj Socha To Aansoo Bhar Aaye” at the other, with the usual yet unusual mujras like “Hone Lagi Hai Raat Jawaan, Jaagte Raho” in between. Then there are the almost free form nazms like “Main Ye Soch Kar Uske Dar Se Utha Tha”, “Dekhi Zamaane Ki Yaari”, and “Koi Ye Kaise Bataaye” that express pathos simply yet most poignantly, thus making themcompletely unforgettable. Add to that the qawwalis that he has penned beautifully for different kinds of situations – romance of “Ye Maana Meri Jaan Muhabbat Saza Hai” and “Dil Gayaa To Gayaa” contrast well with the devotion of “Maula Salim Chishti” of Garam Hawa. Of course there are the usual three line antara structure songs - pretty much the whole gamut of poetry “structures” find their place in his repertoire.

Kaifi sahib’s lyrics traverse a broad range of emotions and exhibit his pen’s versatility on that count as well. Romance, anguish, pathos, patriotism in his songs have already been mentioned before. Add to those the wistfulness of “Kuchh Aisi Bhi Baatein Hoti Hain”, “Chalte Chalte Yoon Hi Koi Mil Gaya Tha” and “Aaj Ki Kali Ghata”, philosophic musings of “Sab Thaat Pada Reh Jayega”, “Badal Jaaye Agar Maali”, and “Zindagi Cigarette Ka Dhuan”, slight suggestiveness of “Mose Chanchal Jawani Sambhali Na Jaaye” and “Jalta Hai Badan”, hope and faith of “Naseeb Hoga Mera Meharbaan Kabhi Na Kabhi” and “Jeet Hi Lenge Baazi”, maternal affection of “Mere Chanda Mere Nanhe”, and we already see the range and sheer talent of Kaifi sahib’s pen. Then there are some obvious songs that one expects from Comrade Kaifi’s pen and these range from the songs in support of farmers (“Jhoome Baali Dhaan Ki Jeet Hui Hai Kisaan Ki”) and all labor classes (“Apne Haathon Ko Pehchaan, Murakh In Mein hai Bhagwaan”) to the obvious slaps on the faces of the corrupt politicians in the form of

भीतर भीतर खाये चलो बाहर शोर मचाये चलो

(Bheetar Bheetar Khaaye Chalo, Baahar Shor Machaaye Chalo)

and the humorous yet biting satire on the state of bureaucracy in the form of

परमिट परमिट परमिट, परमिट के लिए मर मिट

परमिट बिना इस जहाँ में दो दिन भी न जिया जाए

दुनिया से बड़ा तू दुनिया बसाने वाले

तुझसे भी हैं ऊँचे परमिट बनाने वाले

(Permit, Permit Permit, Permit Ke Liye Mar Mit)

While all these are expected from a lyricist and poet of his caliber, he has some surprises up his sleeve too. Consider the pure fun of “Chal Chalam Chal Challam Chal”, a song written for children that subtly conveys the message of Unity in Diversity under the guise of seemingly fanciful lyrics. Then there are devotionals on both sides of the religious lines. On one end he writes songs like “Rakhta Hai Jo Roza Kabhi Bhookha Na Rahega” and “Parvardigara Hum Besahaaron Ka Tu Hi” and on the other end he pens in references from Mahabharat and Ramayan into bhajan like “Ghanshyam Ghanshyam Shyam Shyam Re” and employs both Geeta’s message as well as shlokas in inspirational songs like “Tu Hi Saagar Hai Tu Hi Kinaara, Dhoondhtaa Hai Tu Kiska Sahaara”. Surely signs of an aware individual seeped in fusion culture popularly known as Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb! Though one can’t help but notice that even in such devotional songs, Kaifi sahib’s pen often introduces and even champions basic humanity over and above any religion. For instance consider the last antara of “Rakhta Hai Jo Roza Kabhi Bhookha Na Rahega”. After proclaiming the various merits of a Roza, he eventually writes

रोज़े का ये मतलब है के ख़ैरात करो तुम

भूखों की मदद जिससे हो वो बात करो तुम

And one sees that the humanitarian aspect of the poet’s thought outshines all purely religious narrative – a feat certainly not unexpected from Kaifi Sahib.

In 1995, he stepped in front of the camera for the second time and gave a memorable performance as a lovable grandfather in Saeed Mirza’s film Naseem that was woven around the destruction of Babri masjid in 1992. His earlier appearance was a cameo as himself in Kaghaz Ke Phool in 1959.

His non-film ghazals and nazms have been sung by several big and small names. Biggest and foremost amongst these is Begum Akhtar who sang these in late sixties and early seventies, four seem to be available. In 1977, a private album called Nazrana was released which contains a rich tapestry of commentary by Kaifi sahib woven around progression of a love story punctuated by his ghazals sung by Nina & Rajinder Mehta. A second one, Shaguftagi, was released in 2001 where Udit Narayan, Alka Yagnik, Kavita Krishnamurthy and Roop Kumar Rathod have lent their voices under Khayyam’s music direction. In 2003, Pyar Ka Jashn came out with some nazms and ghazals sung by Roop Kumar Rathod. All of these were personally selected by Shaukat Sahiba but only a few got recorded during Kaifi sahib’s lifetime.

Not only was Kaifi sahib a renowned poet, he was also a playwright par excellence. He was an active IPTA member and served as its all India president. The first play he wrote for IPTA was Bhootgaadi. In 1969, he wrote a play in verse called Aakhiri Shama specifically as IPTA’s contribution to the special Ghalib Birth Centenary celebrations. It was based on Dilli Ki Aakhiri Shama, a modern Urdu classic by Janab Farhatullah Baig that is a fictional account of a mushaa’ira held in Delhi in 1845 under the patronage of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Kaifi sahib further embellished his play borrowing incidents mentioned in Ghalib’s own letters.

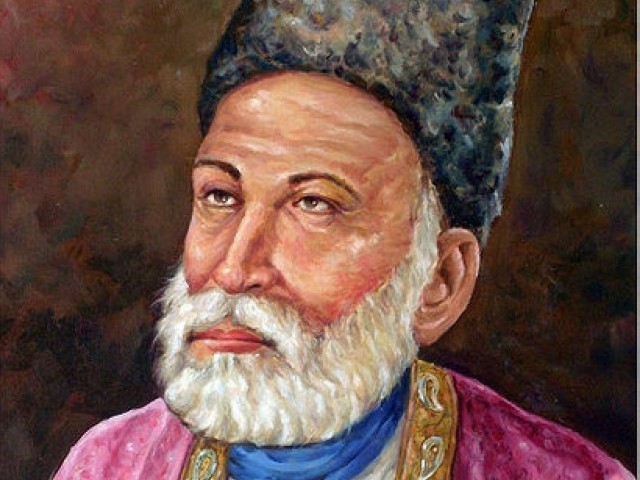

Like many other poetry enthusiasts, Kaifi sahib seems to have been quite fascinated by Mirza Ghalib and was involved with a couple of ”Ghalib” projects apart from Akhiri Shama He provided narration as Ghalib to at least two projects. First was titled Portrait of a Genius where Begum Akhtar & Mohammad Rafi provided vocals to Ghalib’s ghazals under Khayyam sahib’s baton. The second was a short documentary made by M. S. Sathyu that was researched and scripted by Shama Zaidi and had music by Pandit Amarnath of Garam Coat fame. Ustad Amir Khan was roped into singing a ghazal for it, his only one ever, at Kaifi sahib’s suggestion.

Kaifi Sahib is amongst the most decorated literary figures of independent India. He was awarded Padmashree by Government of India in 1974 for his contributions to the field of Urdu literature which he promptly returned. He was also awarded the very prestigious Sahitya Academy Fellowship for Lifetime Achievement in 2002. He also received honorary doctorate degrees from Vishva Bharati University, Shantiniketan, Poorvanchal University and Agra University etc. Afro-Asian Writers Association also awarded him their Lotus award.

Kaifi, the Humanitarian

Kaifi sahib was a communist with dreams and aspirations for a socialist India right from his teenage and worked at grass root level for the party. His paralytic stroke and subsequent brush with death in 1973 added a new sense of urgency to the egalitarian and humanitarian aspects of his personality and he started hankering to go back to his roots – to the village he had left decades ago and had hardly ever visited. Eventually he moved to Mijwan, his native village and was shocked to see time seemed to have stood still for the village. There were no signs of any progress at all, there was not even a road that could lead one to the village.

Kaifi sahib established an NGO, Mijwan Welfare Society, and became a catalyst for rapid change. First step was to get a 2 Km long road built that connected the main road to the village. Next came the Kaifi Azmi Girls School which started as a Primary School but is now a High School and imparts free education to girls. The nearest Railway station, Khorasan Road, was at risk of being closed when Kaifi Sahib started an agitation against that while in a wheel chair and garnered unprecedented support from the locals. As a result, not only was the station spared, narrow gauge line was converted to regular gauge. He also got a Post Office established in Mijwan. As a result, Mijwan is well connected to several important Indian cities by rail and road and the entire world through postal services. The Mijwan Welfare Society runs the Kaifi Azmi Inter College for girls, Kaifi Azmi Computer Training Center and Kaifi Azmi Embroidary snd Sewing Center for Women also. In short, he brought about the transformation of Mijwan from a sleepy, isolated village to a model, modern one.

UP Government recognized his mammoth contributions by naming the road leading to Mijwan, Kaifi Azmi Road and the Highway from Sultanpur to Phulpur, the Kaifi Azmi Highway. The government of India also named the train from Delhi to Azamgarh Kaifiyaat Express in recognition of his colossal contributions. Litterateurs of UP established Kaif Azmi Akademi in his honor while Poorvanchal University, Jaunpur dedicated a Media Center to Kaifi sahib. As a mark of respect, Aligarh University has established a special Kaifi Center in its Library close to where books of its founder Sir Syed Ahmed are kept.

His work today is continued by Mijwan Welfare Society with active involvement from his family, especially daughter Shabana Azmi.

Kaifi, the Personal Face, the Essence of the man

By all accounts Kaifi sahib was a simple living, high thinking, and generous individual, a loving and supportive mate and a doting and understanding father. He practiced what he preached – his real beliefs and life experiences were reflected in his poetry and his actions in real life brought his words alive - there simply was no dichotomy between what he said and did.

Kaifi Sahib wrote Aurat and promised, even provoked women into demanding freedom and equality. In his own personal life also, he fulfilled his promise in many a ways. Shaukat sahiba initially started working as a theatre artiste to provide additional financial support to the family but she genuinely liked her work and was encouraged and fully supported by her husband. She would often be immersed in her character almost to the exclusion of real life and it would be left to her husband to keep things in the house on an even keel. Whenever she was preparing for a new play, Kaifi sahib would provide her cues so as to help her learn and rehearse her lines! Since he mostly worked from home while she commuted even traveled, he took a lot of the household and child rearing responsibilities upon himself. His children Shabana & Baba often accompanied him to his mushaa’iras when Shaukat sahiba would be unavailable due to her work.

His daughter, Shabana Azmi recounts that while he always gave his children unconditional affection and sound advice / guidance, he respected and supported their decisions. He was exceptionally close to his daughter and offered her quiet encouragement irrespective of what choices she made – be it her decision to adopt acting as a career or to go on a hunger strike in support of slum dwellers. His daughter-in-law, Tanvi Azmi, another very accomplished actress, vouches that he always treated her with same respect and affection that he accorded his daughter and she felt more like a daughter than a daughter-in-law, indeed amongst highest of compliments that a father-in-law could ever receive!

Moving outside his family and looking at his work in Mijwan also, it becomes very clear that while he cared about the upliftment of the village and its people as a whole, the girl child occupied a special place in his heart and he went to extra lengths to make sure that they were provided the basic tools to lead an independent life and forge a future of choice.

He spent the last twenty years of his life living almost exclusively in Mijwaan and working tirelessly for its transformation. The man who wrote

प्यार का जश्न नयी तरह मनाना होगा

ग़म किसी दिल में सही ग़म को मिटाना होगा

:

आज हर घर का दिया मुझको जलाना होगा

:

हमको हँसना है तो औरों को हँसाना होगा

actually worked hard to light the lamps in every house of his village and bring a smile to its inhabitants.

In his personal life, Kaifi sahib himself was a man of few needs. He almost never discussed remuneration with any of his “employers” and simply accepted what was handed to him. As a result, it is not unexpected that he amassed no wealth. When he passed away in May 2002, sum total of his worldly possessions were a collection of eighteen Mont Blanc pens that he simply adored, always used for writing and took great care of and a Communist Party of India’s Identity Card! He never owned a house of his own except one that was constructed at Mijwan and was more than happy to donate whatever little savings he had to various causes, Communist Party coffers being the major beneficiaries.

Though a man of few words in real life, he possessed an amazing sense of humor. While his film lyrics and better known and celebrated poetry does not generally tend to be humor laden or funny, his interactions in the recorded mushaa’iras bear a witness to his ready wit and humor. His daughter recollects that he would find a way to make an “April Fool” out of her every year, without fail! He had an amazing ability to mimic people and would weave jokes around his family members that would entertain all of them over and over again.

It became evident to me from several incidents and testimonials that I came across that Kaifi sahib was an optimist to the core, a forward looking man who believed if one makes sincere and untiring effort towards a goal, eventually, the goal is achieved at some point. Even if effort does not come to fruition immediately, one must not give up. His leadership style was also very hands on. If IPTA needed a Ghalib centenary contribution, Kaifi sahib jumped in to write a play. If a railway station needed to be saved from being closed, Kaifi sahib showed up to stir an agitation by camping in the middle of the Railway lines! He was a rare breed - a doer, not just a talker and lead by example.

As mentioned before, he left for his heavenly abode on May 10th, 2002 leaving behind his wife Shaukat Azmi, daughter Shabana, son-in-law Javed Akhtar, son Baba and daughter-in-law Tanvi Azmi along with wider family in the form of the inhabitants of Mijwaan and countless grieving fans and a rich, very rich legacy of poetry, lyrics and above all lessons in humanity. Though he is physically no more with us, he lives on through his works in literature and his NGO. As he himself said in a song he wrote for Pt. Nehru’s last farewell in Naunihaal (and it holds good for Kaifi sahib himself too) - Lives like his should be celebrated, not mourned. Those who live like him, never die.

ज़िंदगी भर मुझे नफरत सी रही अश्कों से

मेरे ख़्वाबों को तुम अश्कों में डुबोते क्यूँ हो

जो मेरी तरह जिया करते हैं कब मरते हैं?

थक गया हूँ मुझे सो लेने दो, रोते क्यूँ हो?

सो के भी जागते ही रहते हैं जाँबाज़ सुनो

मेरी आवाज़ सुनो, प्यार का राज़ सुनो

मेरी आवाज़ सुनो

Long Live Comrade Kaifi!!

Acknowledgements:

My heartfelt thanks to Ms. Shabana Azmi for clarifying some details for this piece and providing insights into Kaifi sahib’s life and personality.

Many thanks to U. V. Ravindra for the beautiful Urdu translation of the Farsi she’r used above

Last but certainly not least, sincere thanks are due to Aditya Pant for providing me Kaifi Sahib’s complete filmography and his painstaking review of this piece.

References:

- Aaj Ke Prasiddh Shaa’ir, Kaifi Azmi published by Rajpal Books

- Documentary on Kaifi directed by A. A. Khan Afridi for NCERT

- Hindi Filmon Ke Geetkaar by Anil Bhargav

- Azmikaifi.com

- urdushayari.in

- IMDb.com

- Myswar.com

- Hindigeetmala.com

- Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema

- rekhta.com

- youtube.com